Levi grew up in southern Arizona and enjoys hunting, photography,…

Are Center Pivots Pivotal for Mule Deer in the Southern Great Plains?

Conversion of native rangeland to row-crop farming is one of the largest forms of habitat fragmentation in the United States, especially the Great Plains. The Ogallala Aquifer supplies water for irrigation in most of the southern Great Plains and is rapidly depleting with estimates indicating less than 20 years before this resource dries up in some areas. This subsidy disappearing will drastically change landscape structure in agricultural landscapes, particularly shifting cropland abundance and crop species planted. Recently, mule deer populations have been relatively stable in most of the United States, but have increased in the Texas Panhandle, an area of extensive row-crop production.

There are only a few instances where agriculturally dominated landscapes coincide with the mule deer geographic range, thus our knowledge of the influence agriculture has on mule deer is limited and drives the desire for research. Many landowners throughout the Texas Panhandle observe sometimes hundreds of mule deer congregating in agricultural fields, however, some landowners did not observe this many deer other times of the year. This led to questions such as:

- Are mule deer traveling far distances to access crops?

- How much time do deer spend in agriculture throughout the year?

- Does agriculture use influence survival?

- Is body condition, antler size, and reproduction affected by this source of nutrition?

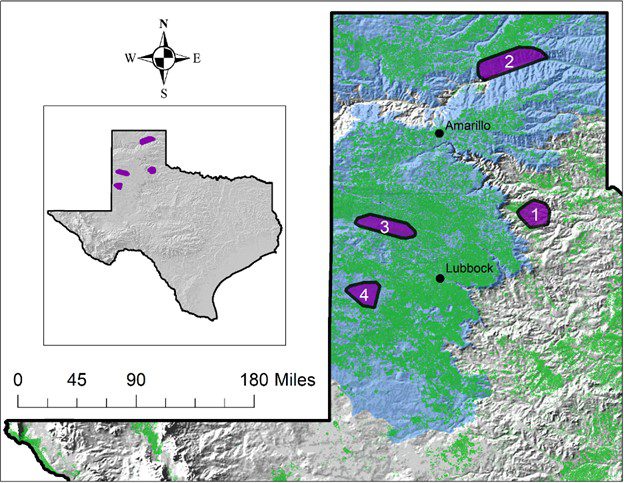

The interaction between cropland and mule deer has not been studied in Texas and is poorly understood throughout the geographic range of mule deer. Thus, it is important to understand these interactions to help the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department better manage these populations as well as provide relatable information to landowners. The Mule Deer Foundation has a long history of providing funding toward research that aids both state agency and private landowner wildlife management in the state of Texas. In collaboration with the Mule Deer Foundation, Boone and Crockett Club, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Wildlife Restoration Program, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Borderlands Research Institute, and Texas Tech University, we began a large-scale, long-term research project evaluating interactions between row-crop farming and mule deer. Our objectives were to evaluate how presence of agriculture influences mule deer habitat selection and link individual level habitat use to body size and population performance. Across four areas in the Texas Panhandle, we captured and radio-collared adult mule deer every autumn and followed their movement and survival for two years. Overall, this project accumulated more than 833,000 mule deer GPS locations from 146 unique adults (69 males and 77 females).

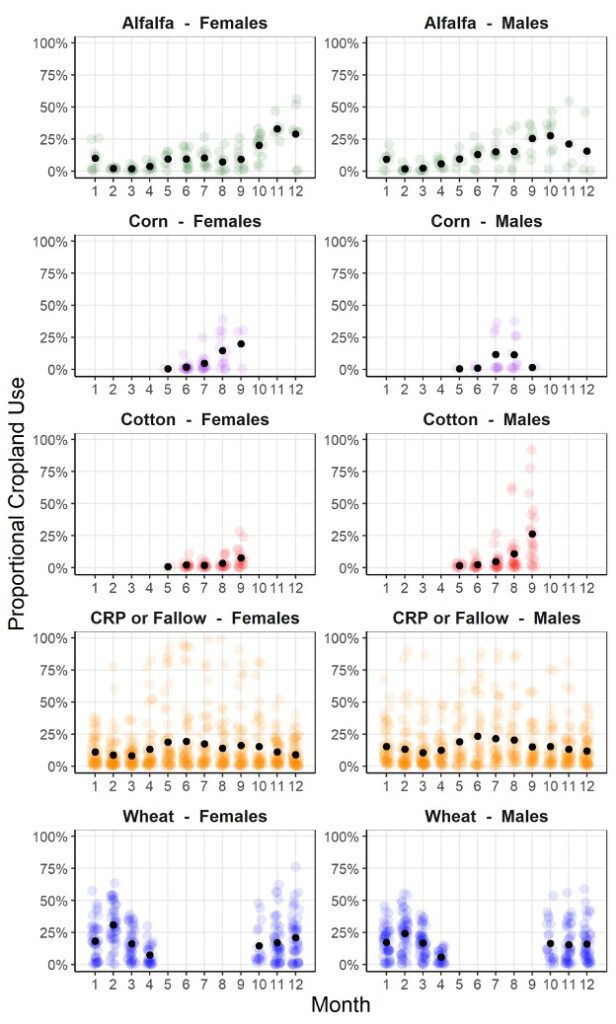

Average annual home range size was 10,000 acres for males and 2,500 acres for females and did not seem to be influenced by agriculture. Mule deer that lived greater than 2.5 miles from cropland did not use agriculture demonstrating that mule deer do not travel great distances to access this forage source. Overall, our collected movement data demonstrated that mule deer spend an average of 3-14% of their time in cropland. The percentage of time mule deer spend in agriculture, however, will vary depending on the time of year and crop species available to them. Our habitat selection models revealed a similar pattern where mule deer were placing their home ranges in areas closer to cropland from January to March for both sexes.

Furthermore, mule deer occurred closer to agriculture during the late summer months of July and August whereas it was avoided for the remainder of the year. When available to mule deer, 25-50% of the population will select early growth alfalfa during all months and 15-25% of the population will select winter wheat during December to March before it reaches maturity. Cotton, milo, and corn selection was very low, and we observed no use of peanuts, soybeans, and potatoes though these crops were rare in our study sites. Mule deer use of agriculture increased proportionally with availability then decreased when more than 20% of the landscape was cropland within a mule deer’s home range. Thus, 20% agriculture may be a threshold defining when agriculture becomes too abundant.

The use of cropland by mule deer had no effect on survival which was consistently high for the duration of the study.

We found no effect of individual use of cropland on antler size, however, males that utilized cropland had greater body condition versus those that did not.

Further, males less than 3 years old that used agriculture exhibited greater body weight and antler size with more cropland use. Agriculture use had no effect on body condition for females, however, agriculture use immediately before and after the rut increased the probability that an adult female successfully produced fawns.

Though our estimates of the time mule deer spent in agriculture were relatively low, access to cropland, even for short periods necessary for foraging, increases individual body condition and population performance. The availability of cropland forage to males enhances their ability to build up fat reserves before the energetically costly reproduction period. Further, use of cropland by females increases the probability of recruiting offspring the following summer, thereby affecting population-level sustainability and growth. We show that even limited use of agriculture has positive effects on body condition and reproduction; however, our movement data indicate that benefits to mule deer are saturated when agriculture exceeds 20% of their home range.

In areas dominated by agriculture, mule deer are faced with an array of human influences. Our research has begun to reveal the cropland density threshold that may negatively influence mule deer, despite the positive influence agriculture has at low to moderate densities. Further, we show how areas of extensive agricultural footprint, which is relatively unique throughout the mule deer geographic range, shapes the spatial ecology of this species. Our baseline population measures will aid in establishing an adaptive management plan for mule deer in the Texas Panhandle, as well as the southern Great Plains as the rangeland-cropland juxtaposition continues to change. Additionally, as policy continues to shape how agricultural practices are performed, state wildlife agencies can adjust their survey methodology and harvest management toward mule deer. The Ogallala Aquifer rapidly depleting only exacerbates the need of linking landscape level factors toward the management and performance of species occupying these regions. Indeed, the combination of threatened water resources and an exponentially growing human population will likely shift agricultural practices in the future. Understanding the influence of human-induced changes on the landscape will further enhance the growing body of knowledge toward human-wildlife interactions and aid all stakeholders in understanding how these landscape linkages act toward one of the most popular big game species in North America.

Editors note: Going into this study we knew that the Panhandle herd was expanding its range over the past 20 years, we are still trying to identify and share the reasons for this. Meanwhile our efforts to bring more water to the deserts of the Trans Pecos continue with two more 10,000-gallon guzzlers being added this past spring. I was pleased to review the 2021 WAFWA Mule Deer Working Group report and discover that out of all the states that mule deer call home, Texas is the only one with a stable population, at least this past year. We will not rest, we will continue to do our best to conserve what we love.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2022 issue of MDF Magazine.

Levi grew up in southern Arizona and enjoys hunting, photography, and fishing. He serves as an Assistant Professor of Research for the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute and is stationed in Lubbock, TX to serve wildlife research and management needs in the southern Great Plains.