California Active Forestry Management Stewardship Agreements

Dave Smith is a freelance outdoor writer with over 220…

Stewardship agreements are increasing the pace and scale of active forest management, a key to mule deer and black-tailed deer habitat conservation in California.

The view up the steep ridge in the morning’s first light was a classic snapshot of the central Sierra Nevada mountains: blue sky, faint stars, snow caps, and talus rock. Rugged country, unforgiving. My legs were burning from the thousand-foot climb from our camp in the meadow, but it was daylight and I still had another half-hour hike up through the boulders. From there, it was an easy jaunt across the bench high on the mountain and I would be in perfect position before Dad started his drive through the willow and alder thickets below. I took a short break to catch my breath.

The morning’s hunt was intimately familiar, even ritualistic. Across the massive canyon, at eye level, was the meadow of Gunsight Pass, where I had killed my first buck, as a wide-eyed boy in this big country for the first time, nearly thirty years ago. Up over the ridgeline was Buck Basin, the site of several memorable hunts. On the far horizon, Soda, the majestic alpine bowl at the top of the world that would always exist in my heart as the yardstick for quality mule deer summer range.

After all these years of hunting the high country in the Emigrant Wilderness of the Sierras, one thing was crystal clear: Nothing had changed up here above timberline. The meadow was a spongy thicket of willows, alders lined the draws, the chokecherry brush patches were robust, and the aspen patches had plenty of young shoots. The high country was resilient.

The first streak of sunlight over the talus reminded me that it was time to get moving. Thirty minutes later my legs were screaming from the strenuous hike up the ridge, but I was in place, ready to take the brisk walk across the flat bench and settle in with a good rest and wait for Dad to make his push. That’s when a movement caught my eye down in the cherry patch a hundred yards below. I slid the pack off and nestled my 6mm rifle in the V of the pack. A nice three-pointer stepped out into a talus opening above the brush patch. The buck looked back down the canyon, in Dad’s direction, then went back to browsing. I locked in, took a deep breath, and squeezed the trigger. Whop. The buck crumpled.

After hustling down through the talus, I found the buck piled up, antlers glistening in the brilliant morning light. That’s when it hit me: This was the exact same spot where I had killed my third Emigrant buck, as a 15-year old freshman in high school. Not just the same canyon or same hillside, but the same rock where I had skinned that buck so many years ago! Soon thereafter, Dad arrived. We drank some water and shared a few laughs, then he came to the same conclusion that I pondered on the ridge earlier that morning: “You know, son, the country looks every bit as good as it did when I came in here with Roger the first time in 1973. I really think we’ll kill bucks here for a long time so long as they can do things to maintain good habitat in the migration corridors on the mid-elevation forests, and on the winter range. Nothing’s changed up here at all.”

The Tuolumne Deer Herd that summers in the Emigrant Wilderness makes its way down the west slope of the Sierras each fall through a series of migration corridors leading to their winter range on the flanks of the mountains. Jawbone Ridge on the Stanislaus National Forest is one of the most important migration holding areas and winter ranges for this herd.

Here’s a look at the issues these deer, and many other deer herds that utilize forested landscapes of California, face in moving back and forth to their productive summer ranges each year – and, most importantly, an innovative approach being used by the U.S. Forest Service, Mule Deer Foundation, and an array of partners are using to turn back the clock to a time of active forest management and excellent habitat conditions.

Forest Management and Deer Populations

Numerous studies have shown that in the Northern Forest Ecoregion, which encompasses the west slope of the Sierras, early successional forests provide excellent mule deer habitat. As stated in the Mule Deer Guidelines for the Northern Forest Ecoregion, published by the Mule Deer Working Group of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, vegetation structure has been modified and nutritional quality has decreased in many forested landscapes: Increasing woody cover in some cases decreases the amount and diversity of herbaceous species. Increasing age of woody shrubs can result in forage of lower nutritional quality and plants growing out of reach of mule deer. Browse plants eventually become senescent and die if not disturbed. As such, active forest and brush management is an important step in making sure deer have abundant forage on their fall and spring migrations, as well as on their winter ranges.

In California, extensive timber harvest in the 1940s and 1950s and subsequent regrowth of browse species resulted in an abundance of early successional forest habitats. This active forest management led to premium habitat conditions for mule deer and black-tailed deer in the 1960s, which coincided with the glory days of California deer hunting when statewide deer populations exceeded 2 million deer with an annual harvest approaching 100,000 deer in some years. In 2019, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) reported that the estimated statewide population had declined to approximately 459,450 deer and the previous season’s total harvest was 28,862 deer. Clearly, forest conditions have changed over the last sixty years and there’s a need for more active management.

Stewardship Agreements

In 2003, Public Law 108-7 granted the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) ten-year authority for stewardship end-result contracting. Stewardship contracting is unique in that it allows the exchange of goods for services, thereby accelerating the amount of forest restoration work that can be accomplished with federal funding. The stewardship contracting authority includes a mechanism known as a “stewardship agreement” which allows conservation organizations to work with the Forest Service and BLM to implement stewardship practices through broad Master Stewardship Agreements and then specific Supplemental Project Agreements. Here’s how it works for MDF: The federal agencies develop non-competitive agreements with MDF in which MDF provides at least 20% of the project costs as match, secures best-value contracts to implement project activities, and, perhaps most importantly to the agencies, can utilize multiple contractors for a single project. Stewardship agreements do not require a goods for services component but that can be helpful to offset costs when timber values are high. The 2014 Farm Bill permanently reauthorized the stewardship contracting authority, including stewardship agreements. MDF has pioneered the use of stewardship agreements for mule deer and black-tailed deer habitat conservation, developing a robust partnership with the Forest Service that now includes Master Agreements with each Region in the West.

In California, MDF has taken the innovative concept to a whole new level through establishment of Supplemental Project Agreements with the Stanislaus, Lassen, Plumas, Mendocino, Eldorado, and Sequoia National Forests. MDF has leveraged the Forest Service commitment to these stewardship agreements with substantial state and private grant funds for a remarkable $15 million in habitat work that is underway!

Stewardship Agreement Projects in California

The Forest Service manages a staggering 20.8 million acres in California and the need for active management has greatly increased in recent decades as a result of excessive fuel loads in the absence of historic fire regimes, insect- and disease-killed trees, and climate change. Stewardship agreements serve as one of many options to increase the pace and scale of active forest management consistent with the agency’s current strategic vision, Toward Shared Stewardship Across Landscapes: An Outcome-Based Investment Strategy.

Stewardship agreements help the Forest Service conduct habitat work for mule deer and black-tailed deer at levels that were not possible in the past. The Forest Service is the #1 agency that can help deer populations because they own and manage the most land. This model of supporting the agency through partnerships, with us bringing substantial grant funding to the table, really accelerates active forest management. If we can create suitable habitat through forest management projects in mid-elevation forests and on winter ranges, we can greatly increase deer populations in California. The summer range is typically in good shape.

The projects are multi-faceted in that they involve conifer removal, brush treatments, meadow restoration, strategic timber harvest, removal of dead and dying beetle-killed trees, and a host of other treatments supported by the Forest Service and partners. Here’s a snapshot of the projects that have been completed or are nearing completion.

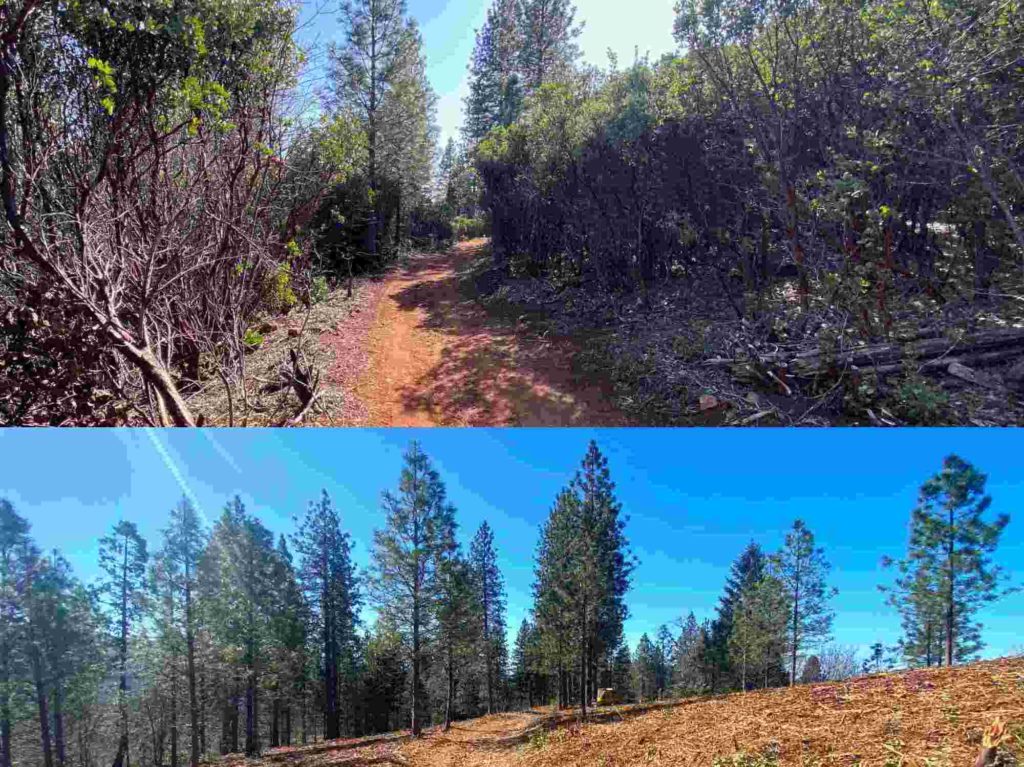

In the Stanislaus National Forest (NF), MDF recently finished a 330-acre project on Jawbone Ridge, the key winter range and migration holding area that was the subject of the legendary wildlife conservationist Starker Leopold’s writings in the 1950s. Jawbone Ridge plays a key role in the annual journey of both the Tuolumne and Yosemite Deer Herds that migrate from the crest of the Sierras to their wintering areas. CDFW historically counted hundreds of mule deer at Jawbone during their winter herd-composition counts but, like many migration and winter range areas, plant succession and other factors has degraded habitat quality over the past few decades. The project was supported by California Department of Fish and Wildlife Big Game Grant Program funding and involved conifer removal and a variety of treatments facilitated by an MDF volunteer crew.

In the Lassen NF, the Manzanita Chutes project is enhancing nearly 600 acres of habitat at the base of Mount Shasta in the X-1 Zone. Mastication is being used to remove dense thickets of manzanita to a manageable level and pre-commercial thinning of conifers is being done to improve forest health. The contractors are opening up areas that will come back to excellent forbs and browse while also strategically maintaining conifers and manzanita as hiding areas.

In the Plumas NF, the Franks Valley project in Zone X-6A represents a powerful partnership between MDF, the Plumas NF, Sierra Pacific Industries, and Honey Lake Power, a 30-megawatt bioenergy electrical generation facility – to reduce fuel loads and improve habitat on 1,300 acres of forest with trees killed by fire, insects, and disease. Rather than piling and burning the dead timber or, worse yet, having it serve as ladder fuels in the next wildfire, the biomass is being used to generate energy under Honey Lake Power’s controlled conditions with filters that remove 95% of the emissions that would otherwise be released into the atmosphere. As such, the project was awarded a grant from the California Climate Investments (CCI) Fire Prevention Grant Program, in which CalFire, the state fire prevention agency, aims to reduce the risk of wildland fires to habitable structures and communities, while maximizing carbon sequestration in healthy wildland habitat and minimizing the uncontrolled release of emissions emitted by wildfires. Stack it all up – mule deer habitat, bioenergy generation, climate change adaptation, and jobs in the rural community of Susanville – and you have a remarkable project!

In the black-tailed deer range of the Mendocino NF, the Letts Lake project is restoring habitat burned in the 459,000-acre Mendocino Complex Fire in 2018. The 300-acre project involves meadow rehabilitation, some commercial timber harvest, and removing dead trees. The Supplemental Project Agreement was signed this March and the project was completed in June.

In the Eldorado NF, the Middle Creek project is restoring an overgrown 800-acre timber plantation to stellar mule deer habitat with thinner timber on the ridges and thicker stands in the bottoms. The project utilizes the approach described in the Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station’s GTR-220 Technical Report, An Ecosystem Management Strategy for Sierran Mixed-Conifer Forests, to produce different stand structures and densities across the landscape using topographic variables.

Finally, in the Sequoia NF, MDF is partnering with the Great Basin Institute and National Wild Turkey Federation on the Eshom Ecological Restoration Project. The project is currently restoring 2,000 acres by removing drought- and disease-killed trees to improve forest health, enhance mule deer habitat, and reduce fuel loads. The project involves hauling the dead trees down to a sort yard provided by the City of Woodlake where contractors grind the biomass into marketable wood products. The project is supported by a $3.2 million CalFire CCI grant to the Great Basin Institute and, like the Franks Valley project, plays a key role in carbon sequestration. Lastly, MDF is implementing the Kirkland Mastication project to restore another 360 acres on the Sequoia NF.

Dave Smith is a freelance outdoor writer with over 220 articles published in national and regional outdoor magazines over the last 20 years. Dave is currently a frequent contributor to Pointing Dog Journal, Retriever Journal, and MDF, and has established his mark as one of the leading upland gamebird conservation writers in the country. His work has also appeared in The Upland Almanac, Wyoming Wildlife, Montana Outdoors, Ducks Unlimited, Pheasants Forever Journal, Mississippi Outdoors, American Waterfowler, Arizona Wildlife Views, and many other magazines In 2015, Dave received the 2nd place award in the Outdoor Writers Association of America Excellence in Craft, Magazine/Conservation contest for his piece, Sandhills and Cycles. He has been a long-time contributor to MDF, specializing in mule deer habitat conservation stories. In his day job, Dave is nationally recognized wildlife conservation leader, serving as the Coordinator of the Intermountain West Joint Venture, a public-private habitat conservation partnership. He lives with his wife, Linda, and kids, Tara, Kyla, and Cole, in Missoula, Montana. Dave spends lots of time mule deer hunting with his kids in the prairie breaks of eastern Montana.