Joining Forces to Remove Barriers

Jessie is a home-grown Idahoan, who grew up working on…

Important herds of mule deer, elk, and bighorn sheep will now have an easier path to follow as they traverse from forested higher elevations down to the lush riparian areas along the East Fork of the Bitterroot River. In the summer of 2021, MDF staff and volunteers from Idaho and Montana joined forces to help improve habitat for herds near Sula, Montana with wildlife friendly fence modification. The area supports priority herds of mule deer and elk that migrate across state lines. These migratory big game spend their summers in the high elevations and riparian areas of Montana, with many migrating back to Idaho to spend their winters at lower elevations on vast sagebrush slopes.

All together three miles of old barbed wire fence were removed in a short two days. There is already a plan to return and remove three additional miles in 2022.

A group of conservation-minded sportsmen and women gathered on the Wetzsteon Ranch in June for the fence modification and removal project. The diverse group was made of volunteers from the MDF Sapphire Chapter, volunteers from Montana Fish, Wildlife, and Parks, along with staff from MDF, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, and the National Wildlife Federation (NWF).

This was the first of several cross-state boundary projects that will remove barriers for big game that migrate between state lines. The MDF along with groups like NWF are able to cross the jurisdictional boundaries, like state lines, and focus efforts on herds that may otherwise not have the attention needed for habitat work. Biologists and local sportsmen have known for years that deer and elk migrate between Idaho and Montana—following a green wave of nutritious forage that helps put on fat before the Idaho winter sets in. Few, however, realized just how many barriers animals encounter on their migratory path, which averages about 45 miles for mule deer and 25 miles for elk. Fences, highways, and other obstructions can be serious barriers to big game, especially younger newborns of the year. A recent study noted that for every mile of non-wildlife friendly fence on the landscape, one big game animal will get entangled each year. How many miles are on the landscape? A 2020 study estimating fence densities in the West determined that mule deer on average will encounter 120 fence crossings each year.

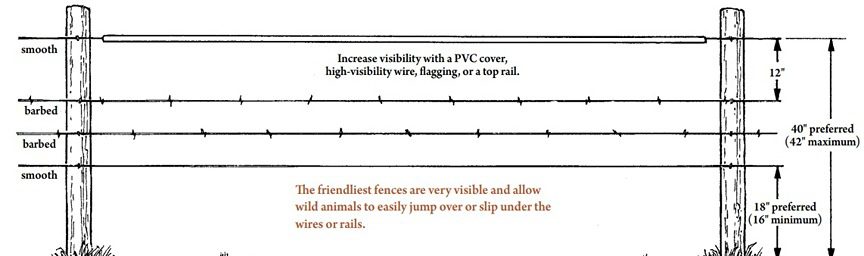

Fences exist on the landscape for a reason and are necessary to contain cattle and other livestock and to mark property boundaries. Fences need to do their job for the producer, but there are options that are friendly to wildlife as well. What makes a fence wildlife friendly? A “wildlife friendly fence modification” is made to be visible and easy to jump over or crawl under without injury. Pronghorn typically don’t jump fences, therefore they need enough space to crawl under a fence. Young mule deer fawns, elk and moose calves, and other young animals also cannot jump over most fences. A fence with a total height of 40-42 inches will be low enough for wildlife to jump over and still high enough to contain cattle, horse, and sheep. Just as important as the total height of the fence is the distance between the top two wires. When animals jump over the top, their back feet can become ensnared, which typically results in death. To prevent this, a simple fix of spacing the top two wires by 12 inches is needed. If possible, a smooth wire on top helps animals from injury as well. For the bottom wire, a height of 16-18 inches is desired to allow animals to pass underneath safely. Also, the bottom wire should be barbless to prevent injury along the backs of animals. Each time an animal runs into a barb, a chunk of hide and hair is taken out that would be helpful for the harsh winters they must endure. For a more in-depth look at wildlife friendly fences, a good source is Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks’ Publication A Landowner’s Guide to Wildlife Friendly Fences.

The Mule Deer Foundation has made removing or converting problem fences along migration routes in the West a priority for years. Volunteers, chapter funding, and donated equipment make fence modifications a reality. All equipment used for the fence removal project on the Wetzsteon Ranch was donated–—the three miles of fence were replaced at no cost to sportsmen or the landowner. Mule Deer Foundation Regional Director Marshall Johnson of Bismarck, North Dakota, made the drive to the East Fork with a donated Dakota Wire Winder that attached to the front of a Bobcat (provided free of charge from Bobcat of Missoula). Mule Deer Foundation Sapphire Range Chapter president Tom Stensatter drove a flatbed trailer, provided by Full Curl Manufacturing of Hamilton, to haul the Bobcat to the ranch. Landowner Bob Wetzsteon donated a tractor and four ATVs for transport of supplies. MDF provided food, Bob provided lodging, and colorful stories were provided for all by Al Gunwall, North Dakota’s State MDF Chair.

Bob Wetzsteon is a fifth-generation rancher on his family’s homestead on the East Fork of the Bitterroot River. Bob sees the trails that grow deeper as wildlife parallel fences too tall for them to jump. He also doesn’t like to see old fences left on public or private land that no longer serve a purpose. Who is left with the burden of removing old fence? Bob was eager to have volunteers remove the fence, and MDF along with partners were eager to step up to the plate. Landowners like Bob Wetzsteon are true stewards of both their privately owned lands and on the public lands they lease. Bob Wetzsteon has deep ties to the land and the wildlife, which makes a difference for his property and his community. You will often hear Bob say, “They were here first” when he explains why he supports wildlife projects on his working cattle ranch. Bob is humble about his commitment to the land, but his impact is obvious when you see herds of bighorn sheep crossing the ranch or hear elk barking at you when you sit in the old homestead yard. You may find Bob serving as a member on a school board, driving the volunteer fire truck, or running a backhoe to help with a willow restoration project. The love of the valley runs in the Wetzsteon family, and the neighboring Wetzsteon ranch was even put into a conservation easement, securing the benefit to both a ranching way of life and keeping the landscape intact for wildlife and the community.

Fence modification projects like these happen because people care, and this would not have been possible without the landowner’s support and his appreciation of wildlife values. Also essential to the success of wildlife projects is the generous support of MDF, partner organizations, and volunteers. Sapphire Range Chapter member Sean Ashby endured the hot days and wrestling with miles of barbed-wire fence, but always with a smile on his face. When asked why he volunteers for MDF, he responded quickly,

“Getting outside and doing projects like this is what it’s all about. Projects like this make huge long-term benefits for wildlife.”

– Sapphire Range Chapter member Sean Ashby

MDF and partners are continuing to remove barriers for migratory big game. Examples of other projects in the works are eight miles of woven wire fence modification in Central Idaho just outside of Leadore, ID. This location has mule deer, elk, moose, and pronghorn that migrate long distances between Idaho and Montana. This same area also has some of the highest fence densities in the northwest U.S. The National Wildlife Federation is also working on projects on the other side of the hill with efforts focused in Southwest Montana—again completing habitat projects for the entire range of these herds that migrate between Idaho and Montana

Jessie is a home-grown Idahoan, who grew up working on her family’s potato farm (“Spud” farm if you are from Idaho). Plant and animal management eventually led to Jessie’s passion for wildlife management, which started at an early age raising cattle, pheasants, horses, chickens, sheep, and pigs. You will find Jessie outside as much as possible, from hunting in Idaho’s backcountry to driving tractors or running chainsaws on habitat projects. Jessie has a 17 year background in habitat work and mule deer & elk management and research. She worked 16 years for Idaho Department of Fish and Game as a research technician and wildlife habitat biologist. Her position with MDF allows leveraging funds and bringing people together to coordinate landscape-level projects in identified critical habitats for mule deer.